Few travel experiences are more uncomfortable than the sharp, stabbing pain that can accompany air travel when your ears won’t “pop.” For many Australians—particularly parents travelling with young children—the fear of in-flight ear pain can turn an anticipated holiday into a source of anxiety. Understanding why this happens and knowing how to manage it can make all the difference between a pleasant journey and several hours of misery at 35,000 feet.

Why Do Our Ears Hurt When We Fly?

Ear pain during flight is primarily caused by pressure changes in the cabin affecting the Eustachian tube—a narrow passage connecting the middle ear to the back of the throat. Under normal circumstances, this tube opens regularly when you swallow, yawn, or chew, allowing air pressure on both sides of the eardrum to equalise. However, when you’re congested from a cold, allergies, or sinus infection, the Eustachian tube can become blocked or fail to open efficiently.

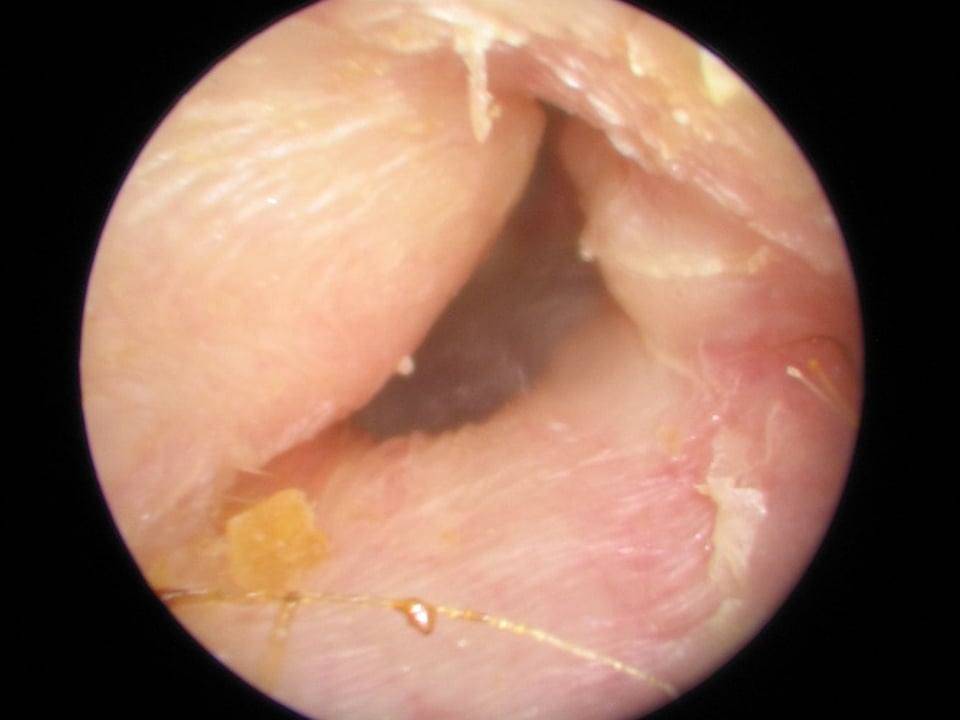

During ascent and descent, cabin pressure changes rapidly. As the aircraft climbs, air in the middle ear expands and usually escapes easily through the Eustachian tube. The real challenge comes during descent, when cabin pressure increases and air needs to move into the middle ear to equalise. A blocked or inflamed Eustachian tube prevents this equalisation, causing the eardrum to be pushed inward. This creates that familiar sensation of fullness, muffled hearing, and potentially severe pain—a condition technically known as aeroplane ear or barotrauma.

Children are particularly vulnerable because their Eustachian tubes are narrower, shorter, and positioned more horizontally than adults’. This anatomical difference means that ear-popping difficulties in children are considerably more common, and young children may not understand how to equalise pressure voluntarily.

Equalisation Techniques That Actually Work

The good news is that several evidence-based techniques can help you equalise ear pressure effectively during flight. These methods work best when started before pain develops—ideally, begin equalising as soon as you feel pressure changes starting.

The Valsalva manoeuvre is perhaps the most widely known technique: pinch your nostrils closed, keep your mouth shut, and gently blow as if trying to push air through your blocked nose. The keyword here is “gently”—excessive force can damage the eardrum or push infected material further into the middle ear if you’re already unwell. You should feel a slight “pop” or relief of pressure. Never perform this manoeuvre forcefully, and stop immediately if you experience sharp pain.

The Toynbee manoeuvre offers a gentler alternative: pinch your nostrils closed and swallow. This creates a negative pressure that can help open the Eustachian tube. Some people find this more comfortable and equally effective.

Frequent swallowing during descent naturally activates the muscles that open the Eustachian tube. Chewing gum, sucking on boiled lollies, or sipping water throughout the descent can encourage repeated swallowing. For infants and toddlers, feeding during descent—whether breastfeeding, bottle-feeding, or offering a drink—serves the same purpose. The sucking and swallowing action helps keep their Eustachian tubes open.

The Frenzel manoeuvre, whilst less familiar to the general public, is favoured by divers and frequent flyers: close your mouth and nostrils and make the motion of saying “K” or “guh” repeatedly. This pushes the back of your tongue upward, creating the pressure needed for equalisation without straining.

The Decongestant Debate: Proceed with Caution

Many travellers reach for oral decongestants or nasal sprays before flying, hoping to keep their Eustachian tubes clear. Whilst these medications can be helpful in specific circumstances, they require careful consideration and should never be used without understanding their limitations and risks.

Oral decongestants containing pseudoephedrine or phenylephrine can reduce swelling in the nasal passages and Eustachian tube opening. However, they also carry side effects, including increased heart rate, elevated blood pressure, anxiety, and sleep disturbance. People with hypertension, heart conditions, hyperthyroidism, or those taking certain antidepressants should avoid these medications entirely. Even for healthy adults, timing matters—decongestants typically take 30–60 minutes to work and last 4–6 hours, so you’ll need to calculate your dose carefully to ensure coverage during descent.

Nasal decongestant sprays (such as oxymetazoline) work more quickly and locally, with fewer systemic effects. A dose 30–60 minutes before your expected descent can be quite effective. However, these sprays should never be used for more than three consecutive days due to the risk of rebound congestion. In this condition, the nasal passages become even more swollen once you stop using the medication.

For children, decongestant use is more controversial. Many paediatric organisations advise against oral decongestants for young children due to limited evidence of benefit and potential side effects. Always consult your GP or paediatrician before giving any decongestant to a child before flying.

It’s worth noting that antihistamines, whilst helpful for allergies, can actually thicken mucous secretions and potentially worsen Eustachian tube dysfunction. Non-sedating antihistamines offer little benefit for pressure equalisation, whilst sedating varieties might make children sleep through descent, which actually prevents the natural swallowing that aids equalisation.

When You Absolutely Shouldn’t Fly

There are circumstances when flying with ear or sinus congestion moves from uncomfortable to genuinely inadvisable. If you or your child has an active ear infection (otitis media), severe sinus infection, or significant nasal congestion, postponing travel is the safest option. Flying under these conditions risks not only severe pain but also potential complications, including eardrum rupture, severe barotrauma, or spreading infection into adjacent structures.

Recent ear surgery is another absolute contraindication to flying, as your surgeon will specifically advise. Similarly, anyone who has experienced a perforated eardrum within the past month should consult their doctor before air travel.

The “two-week rule” is worth remembering: if you or your child has had a significant cold or upper respiratory infection, waiting at least two weeks after symptoms resolve before flying gives the Eustachian tube time to recover normal function. Whilst this isn’t always practical, it substantially reduces the risk of flying complications.

Pressure-Regulating Earplugs: Do They Help?

Specialised earplugs designed to regulate pressure changes during flight are available at most pharmacies and airport shops. These devices, marketed under various brand names, contain a ceramic filter that slows the rate of pressure change experienced by the eardrum.

The evidence for these products is mixed but generally positive for people with mild Eustachian tube dysfunction. They won’t overcome complete blockage, but for travellers with marginal problems or a history of mild discomfort, they may reduce symptoms. The key is correct insertion well before descent begins—ideally before takeoff—and leaving them in place until after landing when cabin pressure has fully stabilised.

For children, sized versions are available, though getting young children to tolerate earplugs can be challenging. They’re generally most practical for school-age children who understand the purpose and can tell you if they’re uncomfortable.

When to See Your GP

If you’re planning air travel and have concerns about ear pressure, particularly if you have a history of ear infections, chronic sinus issues, or episodes of severe ear pain while flying, a consultation with your GP before departure is worthwhile. They can examine your ears and nasal passages, assess Eustachian tube function, and advise whether it’s safe to proceed with your journey.

You should definitely seek medical attention after flying if you experience:

– Severe or persistent ear pain lasting more than a few hours after landing

– Noticeable hearing loss that doesn’t resolve within 24 hours

– Vertigo or significant dizziness

– Fluid or blood draining from the ear

– Ringing in the ears (tinnitus) that doesn’t settle

– Symptoms of infection, such as fever

These signs may indicate barotrauma requiring assessment and treatment, or potentially an ear infection that has developed or worsened during travel.

Practical Steps for Families

For parents travelling with children, preparation makes an enormous difference. Here’s a consolidated approach:

Before the Flight:

– Avoid scheduling flights when your child has active cold symptoms if possible

– Pack sugar-free gum for older children, boiled lollies, or a favourite drink

– Prepare bottles or snacks for infants and toddlers

– Consider consulting your GP if your child has frequent ear infections or a current cold

– Explain to older children what will happen and how swallowing helps

During the Flight:

– Stay awake during descent, this is crucial for effective equalisation

– Begin equalisation techniques as soon as descent starts, not when pain develops

– Keep children engaged and encourage frequent swallowing

– Feed infants during descent when possible

– Stay calm if your child becomes distressed, anxiety can make them hold their breath, worsening the problem

The Role of Audiology in Ongoing Ear Health

For travellers who experience repeated problems with ear pain flying despite following all recommended strategies, an audiological assessment can identify underlying issues. Tympanometry—a quick, painless test—measures how well the eardrum moves and can detect persistent middle ear fluid or Eustachian tube dysfunction. This objective measurement helps distinguish between temporary congestion and chronic problems that may benefit from medical or surgical intervention.

At The Audiology Place, we regularly see patients whose travel-related ear problems are the first indication of underlying Eustachian tube dysfunction, undiagnosed allergies, or chronic middle ear issues. Whilst we can’t provide medical treatment for infections or prescribe medications, we can thoroughly assess your ear function, counsel you on management strategies, and refer appropriately to ear, nose and throat specialists when indicated.